No doubt plenty of researchers over the past couple of years found themselves sat on a chair, empty coffee cups strewn about, rubbing their digitally-tired eyes and (constantly re-)wondering “what now?!”. This blog hopes to provide some practical insight into how we supported the participation of people living in poverty in Poverty Alliance’s Get Heard Scotland project. Reflections and insights around recruitment and supporting participation and the responsibilities of researchers when conducting research digitally on poverty during the pandemic are shared.

Although the team was presented with an abundance of professional and personal challenges, we were also able to expand our digital repertoire, and pave access for individuals who had not engaged with research before to feel comfortable and able to do so. We were acutely aware of the ineffectual term of ‘hard to reach’ and worked consciously to create pathways to engage that responded to the challenges people were facing.

Recruitment and Engagement

We developed two tools to support recruitment and participation to expand our reach: a media pack and a chat pack.

Media Pack

The media pack was directed at Local Authorities, charities, grassroots groups, and other third sector organisations who were working directly with those we hoped to speak with. The media pack was a collection of twitter threads, Instagram stories, graphics, hashtags, pre-written e-mail invites, and suggested text messages. This was done to address both the limited capacity of organisations and to ease the circulation of our recruitment callouts, as well as ensuring consistency in messaging across platforms and groups.

An underwritten though fundamental aspect of research, the meta-data (data about how we collected data), for this project was: over 250 organisations and people were contacted, with resultant participation of 32 families. It took over a month of continuous phone calls, e-mail exchanges, texts, and e-public speaking to get our recruitment engaged with.

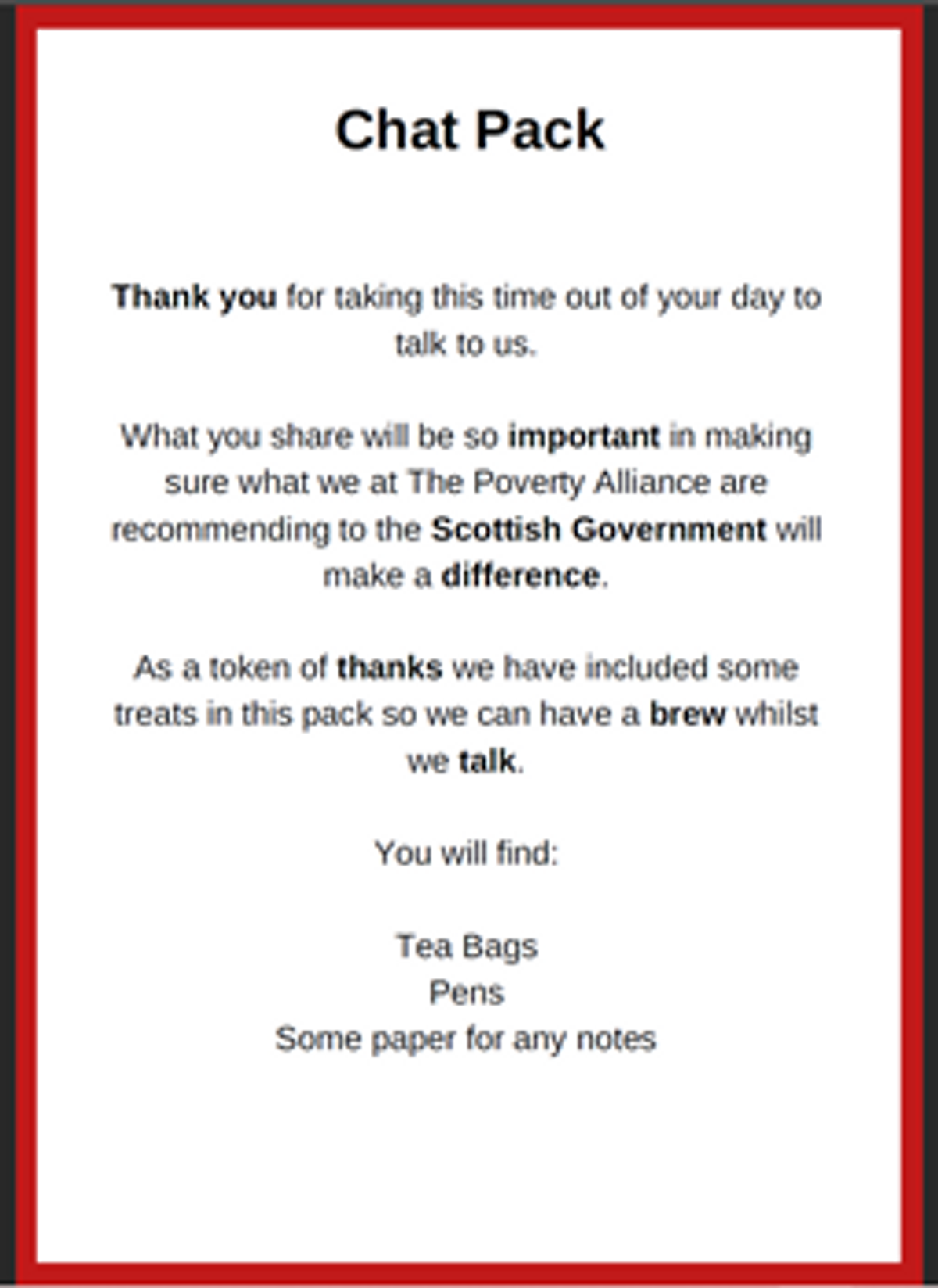

Chat Packs

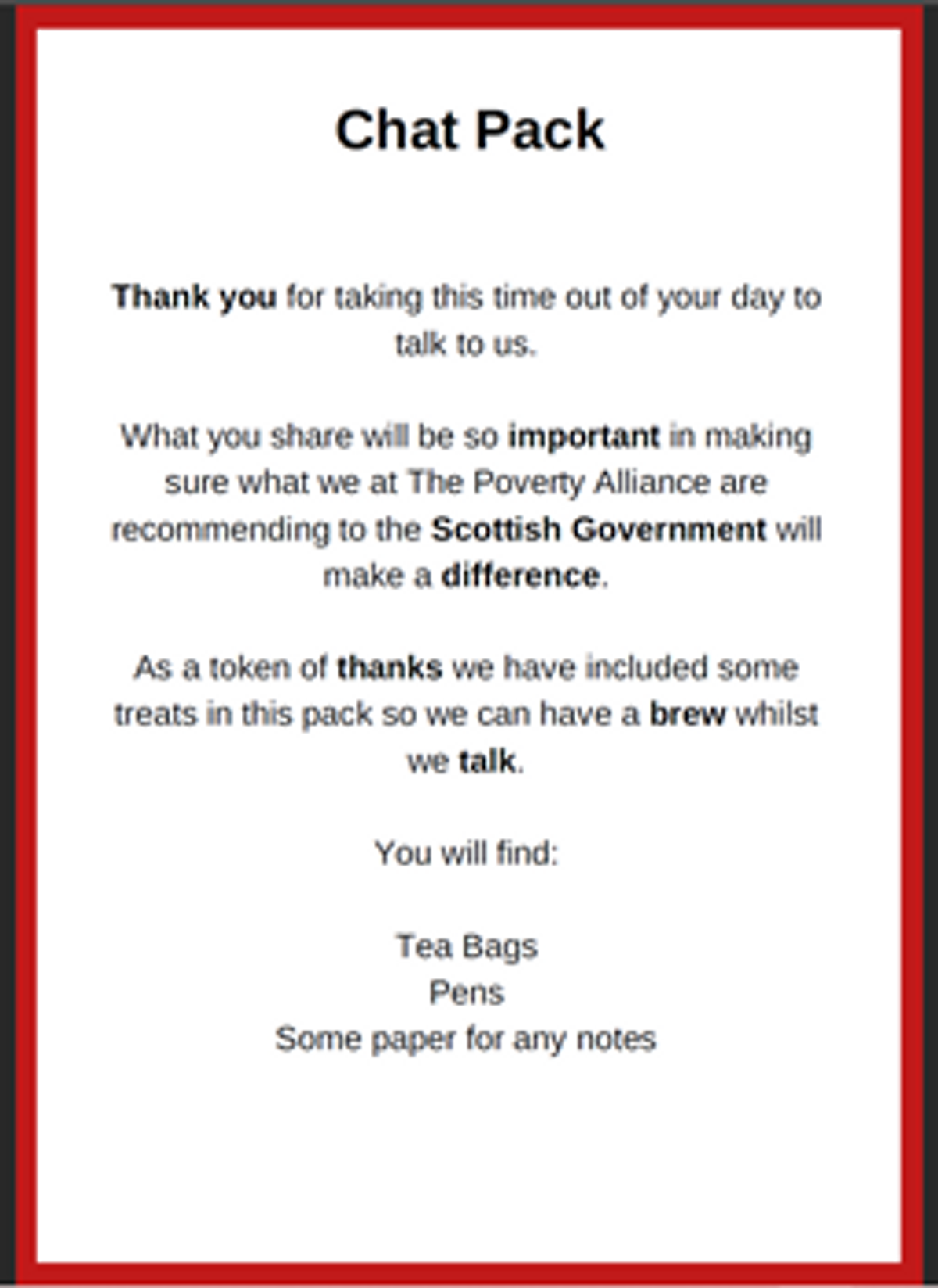

The second collection developed were the chat packs. These were pre-delivered to all those who agreed to participate prior to interview. It consisted of a notebook, pens, teabags, a thank you, and a list of useful contacts. We were mindful of the often stunted, sometimes rhythmically jolted nature of distanced, digital research projects. We, in part, addressed this through creating a memento of participation, an item with which to support the actual interview, and a document that can continue to support beyond the remit of the project itself.

Safety and care for participants

We made an incredibly high number of safeguarding care-referrals during this research project. A combination, we believe, to be the result of cumulative lockdowns, intensification of poverty, exacerbation of loneliness and mental ill-health, and overwhelmed services. Sometimes the Community Researcher was the first person someone had spoken to in a while. And there was a relieving aspect to the relative anonymity of the participant – we had never met in-person, we spoke over the phone (only three people wanted to video call), and there was a brief period of prior contact.

But, this also posed some challenges – especially around ensuring participant safety which relied upon training, and not only the supportive but highly skilled safeguarding colleagues on the team. It was difficult to assess risk and safety over a single phone call.

We created a ‘useful contacts’ document which has now become a staple in our Community Researcher’s toolkit. We gathered local and national support organisations and listed their numbers (trying to include a freephone number), e-mails, opening hours, and their purpose. We covered a range of services based on themes cropping up in scoping work; these were men’s violence against women, social security and care services, like winter heating and crisis funds, free food organisations, local mental health groups and children’s organisations. This was part of our contribution to support the ongoing safety of those we spoke to.

Supporting continued participation in the pandemic and beyond

The appetite to engage with research over this period was a cause and consequence of the overwhelmed nature of our connecting community organisations, and the energy required to recount the difficultly of living on a low income. However, we did connect with those who haven’t taken part in research before, based on feedback received.

We adopted a variety of digital methods to overcome a single way to participate. We offered video chat, audio call, and digital diaries, and were explicitly open about welcoming other options. Most people opted for an audio call. The team would always call so to incur the expense of the hour-long interview. We would send a follow up text to check-in and thank the participant too.

To thread participation throughout the process, we hoped to develop group co-analysis sessions with those who agreed to take part. The varieties of life and the limited time to complete the project meant we couldn’t host the initial plan of a digital group to feedback and analyse together. Instead, we adopted 1-2-1 co-analysis sessions with six people, who gave feedback on what our findings were showing- meaning our recommendations were directly based on lived experiences. A challenge of this was around ensuring a variety of voices, so not to homogenise results based on a particular lived experience.

Outwith this specific research project, we also invited participants to continue their engagement through joining the Poverty Alliance’s Community Activist Advisory Group, as oftentimes research can come to an abrupt start and stop for participants.

Conclusion

To conclude, we finish with a brief practical guide inspired from our research journey with Get Heard Scotland:

- Create an excel document with different pages outlining your contacts. This will become your vital contact page where you can log when you contacted who, their response, their agreement to future involvement and their socials.

- Create a social media and chat pack.

- Create a ‘useful contacts’ document.

- Be prepared to repeat calls, re-send e-mails and continuously follow-up organisations and participants to engage.

- You will contact way more people than will engage.

- A significant amount of time will be spent on creating networks to join in the research.

- People’s schedules are busy, so be flexible and have a Plan B.

- Offer different ways people can participate. We use video calls, audio calls, and digital diaries. Be open to different methods of engagement.

- Reimburse participants.

- Remind the participant a day before, and an hour before you are scheduled to meet.

- Send a follow-up message of thanks, detailing how they can get in contact further. This will also be on the information they already have in the information and consent documents.

Biography

Beth Cloughton is a PhD researcher at the University of Glasgow and was The Poverty Alliance’s former Community Researcher on Get Heard Scotland. Twitter @b_researcher, e-mail b.cloughton.1@research.gla.ac.uk

Links

Get Heard Scotland Report can be found here: https://www.povertyalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/TPA_GHS_Project_Research_Report_FINAL_proof_02-1.pdf

Get Heard Scotland features in a cross-research project collaboration with COVID Realities, which can be accessed here:https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/covid-19-collaborations